I was sixteen when my father died. I could scarcely remember his face, since I was 10 years old when last I saw him. That’s when I left Jamaica to attend school in Norway. Yet, while his visage was a sunny-somewhat-mythologized blur, the memory of the day he died remains stark…

I was thinking, in class at Kvinnherad videregående skole, about how my little sister Nilla Brit had annoyed-the-faen out of me the entire morning.

Thinking about testing the teeny bit of sexual angst that had morphed into a full blown hormonal itch on Per Gunnar, the shy 6’3” 15-year-old redhead with the incandescent irises, bullet nose, and waiting-to-exhale gait who everyone called “spesiell” because of his tendency towards all things religious.

Thinking about last weekend’s Russefeiring and trying out the hangover cure bestevenn min had recommended.

Thinking about the Russe trip to Copenhagen and wondering in vain if my Norwegian-Saami mother would loosen her loving yet overprotective grip and allow me to go.

Thinking how my functionally illiterate highly perceptive adoring fundamentalist Pentecostal Jamaican mother would be disappointed in the me that I had evolved since she saw me two years prior.

Thinking about where to place the guilt of not calling her for the last three Sundays out of a genuine fear that I would out myself during the question and answer portion of our weekly samtaler.

I was not thinking about my father, who had fallen into a diabetic coma three days prior. I was not thinking about how the years of destitution in Jamaica had forced my father to repeatedly choose between his insulin and feeding his three daughters. I was not thinking about his fear of going to the emergency room when he began feeling the cold clammy delirium, the accelerating heartbeat and blurred vision that accompanies rapidly decreasing blood sugar.

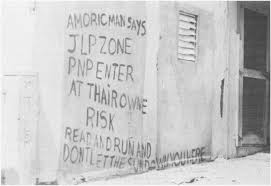

I was not thinking about the fear that gripped my father at being deported because he had overstayed his non-immigrant B1 visa and had been working illegally in the country for the last 5+ years. Nor was I thinking of the fear my father had even during the Reagan Amnesty years, when he could have sought asylum based on his status as a political refugee who had been shot multiple times because he was audacious, and desperate enough to seek employment in a Peoples National Party area of Kingston, while living in a Jamaica Labour Party garrisoned slum.

I was not thinking that he had gone from a racialized class system in postcolonial Jamaica, where his color, class, and lack of education defined his marginalization; to one in Queens NY, where race, class, and national identity had structured his position on the margins, where his fear materialized into a legitimate barrier to him seeking the medical help he desperately needed.

I was not thinking that he had gone from a racialized class system in postcolonial Jamaica, where his color, class, and lack of education defined his marginalization; to one in Queens NY, where race, class, and national identity had structured his position on the margins, where his fear materialized into a legitimate barrier to him seeking the medical help he desperately needed.

I was not thinking how these systems of oppression, that existed in both locales, had conspired to limit his access to adequate healthcare, healthy foods, and clean air; all but ensuring that diabetes would become trauma reproduced across multiple generations, affecting every member of his, and now my extended family.

I also did not think he would die at 45, within three days of falling into a diabetic coma, alone in a hospital bed, in Queens NY.

Unlike my often-mythologized memory of my father’s face — the data is crystal and irrefutable — the novel coronavirus has exposed how little things have changed for people of color, the working class and the poor in this country. And, for all the claims that the novel coronavirus is an equalizing force, COVID-19 has, and is, taking a disproportionate toll on non-white bodies.

Centuries of segregation in densely populated areas, lack of access to quality healthcare, clean air and drinking water, nutritious food choices, overrepresentation in frontline/first responder/essential jobs — where they are not able to capitulate to the fight-or-flight instinct seen across the country as those that can, do flee the epicenters of disease — have made the bodies of ethnically and racially-minoritized peoples more vulnerable to the pathogens pathway.

The coronavirus has exposed our reticence to reckon with, and honestly confront systems of oppression that have weaponized social categories of race, class, and national origin. This reticence has repeatedly positioned people of color, the poor, and working classes at the gaping mouth of diseases with insatiable appetites for vulnerability. This was the case in 1918, it was the case for my father in 1993, and it is the case today.

Yet, it does not have to be going forward…

Coming soon: The Color of COVID Part Two: Making social equity central to combating corona

Header image credit: Arts of Boston

Top photo: Norwegian high school seniors Russefeiring in traditional red overalls.

Bottom photo: A partisan warning written on a wall in Kingston Jamaica during the election wars of 1980.

Nicole “Nicky” Hylton-Patterson joined the ANCA family as the Director for the Adirondack Diversity Initiative (ADI) in December 2019. Her journey from St. Catherine, Jamaica to Saranac Lake is one marked by lengthy sojourns in Trondheim, Norway, Elmira NY, and Tempe, AZ. A relentless advocate for justice and equity, Nicky brings 20+ years of experience as a community organizer, educator, activist scholar and diversity & inclusion subject matter expert and practitioner to the role.

Nicole “Nicky” Hylton-Patterson joined the ANCA family as the Director for the Adirondack Diversity Initiative (ADI) in December 2019. Her journey from St. Catherine, Jamaica to Saranac Lake is one marked by lengthy sojourns in Trondheim, Norway, Elmira NY, and Tempe, AZ. A relentless advocate for justice and equity, Nicky brings 20+ years of experience as a community organizer, educator, activist scholar and diversity & inclusion subject matter expert and practitioner to the role.