Like many contemporary holidays and celebrations, Thanksgiving has become a holiday where oversimplification, misrepresentation and myths tend to dominate the narrative. The history and significance of the day is often overshadowed by commercialism and merry-making. Holiday shopping and Black Friday sales, which increasingly begin on Thanksgiving Day, have become a distraction from the celebration of family and togetherness.

Furthermore, when it comes to Thanksgiving, there is a deep and tragic history that for centuries Americans have refused to accept — choosing instead to perpetuate a harmful myth. Unlike the depiction in the 1912 painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, the relationship between the Wampanoag Tribe native to Massachusetts and the Pilgrims of that “First Thanksgiving” was anything but the school-taught myth of happy little Indians and Pilgrims sitting together enjoying a meal. In my school days, the lesson was taught with construction paper feathers, pilgrim hats and books where “I was for Indian” was accompanied by colorful images of smiling party guests.

For many of us with Native American ancestry (mine being Anishinaabe), Thanksgiving is at least complicated, if not impossible to celebrate in a traditional sense. Even though family and gratitude are deeply rooted in most tribal traditions, what makes the holiday most challenging is the often hidden or deliberately ignored historical reality of what followed for the Wampanoag, as well as the eventual colonization, dispossession and slaughter of entire nations of people. I can’t ignore that.

When looking through the lens of all that Indigenous people have endured, it’s easy to understand why many look at Thanksgiving as a “Day of Mourning.” But also why others choose to celebrate the day as a reminder of their cultures’ survival. Even after all that has happened since 1621 — war, disease, colonization — Indigenous people are still here: the Haudenosaunee, the Abenaki, the Anishanabee, the Tolowa, the Akiak, the Coquille, and hundreds of other tribes. Even the Wampanoag are still here, still on their ancestral homelands, still practicing their traditions. I’d say that is something to celebrate — maybe just not under the current banner of Thanksgiving Day.

So how do Native Americans celebrate Thanksgiving? It depends. Some ignore it completely, some protest, some powwow, some gather with friends and family and eat turkey and watch football, and some hit the malls. But I don’t know of anyone who tells the myth of the First Thanksgiving.

You can help rebuild a Thanksgiving that works for all.

You can actively challenge the harmful and devastating myth that covers up the truth of our complicated and tragic history of the colonization of Indigeneous communities across what is now the United States. In gathering with friends and family, you can start a new tradition of taking time to remember that, no matter where you live in the United States, you are on Indigenous land, enjoying a dinner that likely includes Indigenous foods. You can educate yourself on the tribes in your area, their histories and traditions. You can support your neighbors and empower yourself by facing and understanding the truth behind the origins of the Thanksgiving holiday and the damage and pain this celebration causes for many.

If we begin to deconstruct how we celebrate this day, we can rebuild it into something better — something real and genuine and healing. We can take the best of the day — the family, friends, food and gratitude — and move forward, creating a celebration for which we can ALL be thankful.

To learn more about the origins of Thanksgiving Day and the wide range of Native American perspectives on the holiday, please visit these resources:

Do American Indians Celebrate Thanksgiving?, Smithsonian Magazine

The Thanksgiving Tale We Tell is a Lie. As a Native American, I’ve Found a Better Way to Celebrate the Holiday, Time Magazine

Rethinking Thanksgiving Celebrations: Native Perspectives on Thanksgiving, National Museum of the American Indian

Please read the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address, which is recited by Native American communities throughout the year, not specifically for the Thanksgiving holiday.

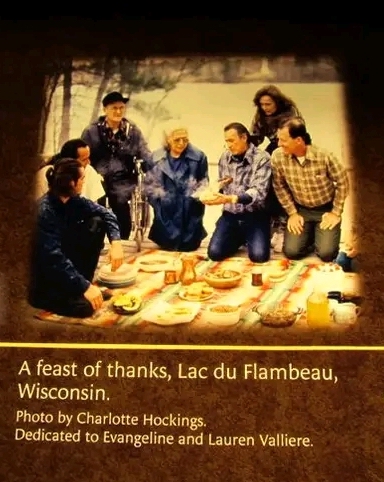

Photo: An Ojibwe exhibit in the Smithsonian Museum of the Native American features members of the author’s family sharing a “feast of thanks.”

Melanie Reding is Associate Director of the Adirondack Diversity Initiative, a program of ANCA.