The Federal Reserve Bank of New York. It’s got the largest known deposits of gold in the world – in the vaults 80 feet below ground, resting literally on the bedrock of the Island of Manhattan, 50 feet below sea level. At 6,350 tons, that’s a lot of weight. Here is what it looks like:

And in case you were wondering, it’s all worth about 254 billion dollars. Yes, $254,000,000,000. (I know, I had some ideas about how to help the Adirondack North Country economy with just a handful of gold bars too. Each one is worth about $500,000.)

I was there recently, at the Bank, not to tour the gold vaults (which you can actually do), but as part of a new Community Advisory Group (CAG) composed of leaders of nonprofit and community organizations from throughout the Federal Reserve’s Second District (New York State, Northern New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands). The CAG’s primary goal is to provide the New York Fed, including President William C. Dudley, with a more thorough understanding of the economy’s impact on communities and individuals.

There are 12 members of this group, and we met for about four hours to get to know the workings of the Bank, hear the Bank’s most recent economic analyses and hear perspectives from each of the members of the group. They asked me to make a short presentation about the Adirondack North Country economy, based on views from the ground.

I talked to a lot of people across the region – thank you! – to prepare comments.

Sitting in an ornate and elegant board room in the Italian Renaissance-style Federal Reserve building in lower Manhattan, my biggest challenge was to convey the peculiar, wonderful, challenging and unusual characteristics of the region. How do you create a visceral connection to the truth of the place and its people? Its sheer size – a bit larger than Switzerland – and its small population. The perseverance and resourcefulness of the people. The kindness of our communities. The day-to-day struggles of towns that have lost their biggest employers; the drug addiction and breakdown of families that result. The grittiness and creativity of the innovators. The long cold winters and long winding commutes. The consistent difficulties in getting access to capital.

What makes this rural region utterly different from other rural places is the fact of the splendid, complicated and natural wealth of the Adirondacks right in the middle of everything – at 6 million acres, that is 1.5 million acres larger than the entire state of New Jersey. Writer Verlyn Klinkenborg describes it well in a 2011 National Geographic Magazine article:

Here, the outside world seems to vanish behind enfolding mountains, quarantined away by river, still water, and wetland. Crest one of the High Peaks, and all you see is Adirondacks… When the Adirondack Park was established in 1892, it was intended to be a preserve, not an experiment. And yet the park has become an inadvertent laboratory exploring the coexistence of a nature preserve with a resident population of some 130,000 humans and millions of summer visitors. The biological experiment has been an unqualified success – biodiversity is rebounding – but the social and economic experiment is ongoing.

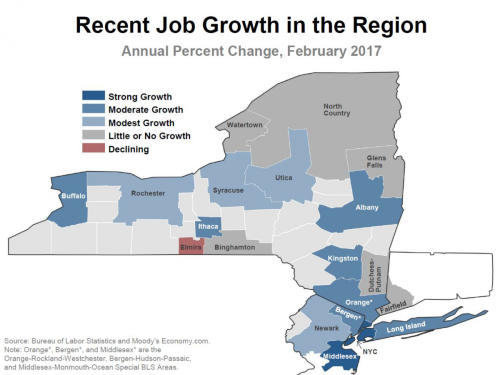

Making a success of this social and economic experiment is of paramount importance. When you look at the economic numbers for the region, including the Adirondacks, the story is bleak.

But when you talk to some of the new pioneers who are starting to populate the region, bringing small scale farming and value-added food production back, starting innovative systems for year-round covered organic farming, creating small high-tech businesses that meet regional and national needs, scaling up artisan product production, growing clean energy production – a different picture starts to emerge.

My interviews with start-up businesses in the region divulged some fascinating patterns. Where start-ups were not able to qualify for conventional financing, citizens from some communities stepped forward to offer loans. Some cited place and its unparalleled quality of life as the reason they would only start their businesses in this region. They believe that they can attract highly qualified employees based on the rich natural and social capital in the region.

I started to think about the notion of wealth and capital and what that means in today’s rural economies. The dictionary’s definition of wealth includes “an abundance or profusion of anything.” By that definition, we have wealth that is unheard of in New York City, despite all the the gold in the basement of the Fed building. Clear abundant water bubbling up year round from ancient bedrock, clean air from billions of trees, tenacious and caring communities, daily access to trails and lakes and mountains, wealthy soils that produce ridiculously healthy food, deep connection to wild landscapes and views that feed the soul, fellow citizens who embrace the inherent quirkiness of the people who have figured out how to live and work here.

The good news is that this region is on the radar of those who are invested in rebuilding economies and are interested in hearing from us. The Adirondack North Country matters. The challenge is how we grow the economic opportunities in this region, how we redefine and embrace our own economic, social and environmental wealth in terms that are not just about dollars but about the value of natural and social capital. That is perhaps the most critically important thing we can do in this world that has gone crazy for the narrowest definition of wealth – “a great quantity or store of money” – at the expense of everything else that human and natural communities need for survival.

* “All That is Gold Does Not Glitter” is a poem written by J. R. R. Tolkien for his novel The Lord of the Rings.